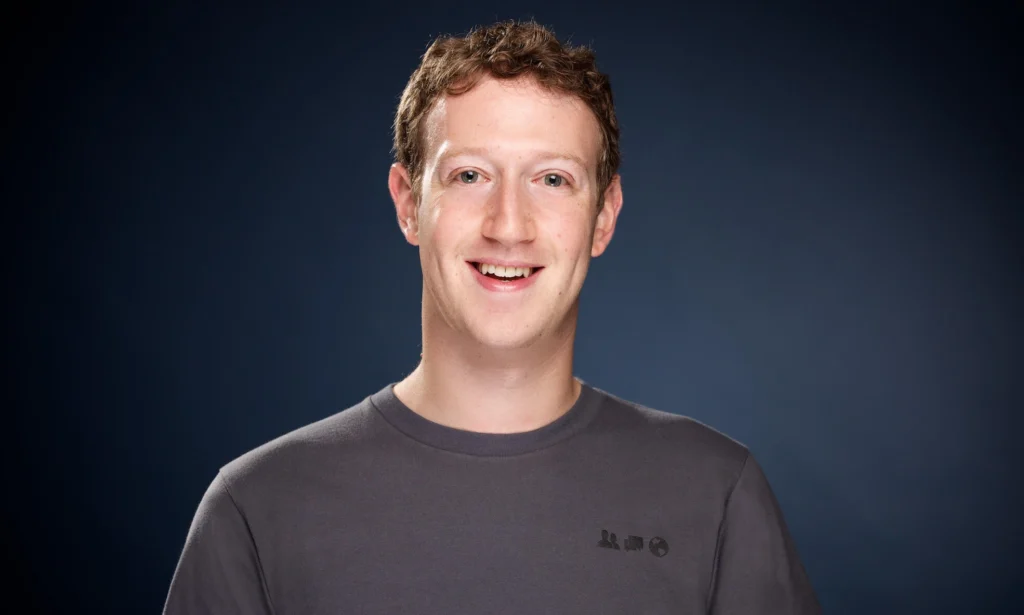

Tim Smith

A Photographer's Lifelong Journey into the Hutterite Community

By Alhanouf Mohammed Alrowaili

Photography is a great way to document great and important projects or events that matter in the world, especially if it’s related to history, culture or heritage. Tim Smith is a documentary photographer based in Brandon, Manitova. He presents an exhibition based on his work photographing the insular, communal Hutterites of North America over the past fifteen years. What began as a simple encounter with members of Deerboine Hutterite Colony in the spring of 2009 has grown into a multi-layer long-term documentation of Hutterite culture. The Hutterites, communal anabaptists, immigrated to Canada from the United States in the early 1900s, following centuries of upheaval and migration through Europe beginning in the Tyrol region of Austria. The past century in Canada and the United States has been one of the most peaceful and successful periods of their history, yet brings its own challenges to their culture.

His work has been supported by several grants and has been exhibited throughout North America, Europe, Asia, The Middle East, Australia and Africa. Recent exhibitions include the 2023 Xposure International Photo Festival in the United Arab Emirates, Freelens Gallery in Hamburg and FotoForum Innsbruck.

The project was also chosen for the 2022 DongGang International Photo Festival – Artist of the Year solo exhibition. In addition to exhibiting, excerpts from my Hutterite work have been published widely in print and online. This body of work represents one of the longest and broadest photographic documentations of the Hutterites ever produced. Smith is a supporter of the Coalition for Women in Journalism.

Portions of Smith’s Hutterite work have been graciously supported by four Manitoba Arts Council grants and a Canada Council for the Arts grant.

1) Why did you pick these projects to cover?

I’m from where I live now, and I’m from a small community in the middle of the Canadian prairies, so there is lots of farming, and not around where I live. And I was looking for some sort of long-term project that I could take on when I accidentally got introduced to a Hutterite colony that lives about 20 minutes from where I live.

So, I went out there to take some pictures and I just became really interested in their culture and I wanted to learn more, so I just kept going back, thinking maybe I would spend six months, a year or maybe two years on a long-term project. And now it’s been more than 14 years that I’ve been doing it.

2) Are all your projects done in the same locations, or you have to travel?

I wouldn’t say that I’ve traveled most of my work around the world. You know, I have traveled a little bit, but most of my work that I do and that I’m known for, I do very close to home. So mostly in Manitoba, Canada.

3) What have you seen in them that captured your camera for many years?

Because they do live very differently than I do and most people in mainstream society, but the more I got to know their culture, I became more interested in finding the connections that people would see between their community and our community, because I think connection is so important in the world right now. We seem to be becoming increasingly disconnected, especially after COVID-19, when we couldn’t visit our loved ones. We were stuck in our own little worlds. And that has done a lot of damage to the idea of community and connection. I think we forget how important that is. The Hutterites offer such an amazing example of community and connection among them. So, I really admire that, and I’m really drawn towards documenting that.

4) Have you become close with them, like backgrounds, personal stories and what happened to them before and after COVID-19?

Yeah, absolutely. You know, a lot of the colonies that I visit are within an hour’s drive from where I live. And over the years, these people have become my close friends, and they’re very important to me. Beyond the project, I love visiting them. Every day, I get to spend time socializing or photographing. And one of the reasons I’ve spent so long doing that is to ensure that my documentation is as broad as possible, telling a complete story about Hutterite culture as possible without leaving anything out.

5) Did your documentaries change anything in their lives?

No, I think if any, the Hutterites are very self-sufficient and very, what’s called a closed society, so they live apart. And a key aspect of their survival over the last 500 years is their ability to be apart from mainstream society. So, this isn’t a project where, you know, sometimes as journalists, we tell stories that need to be told, that can help someone, that can shine light on an abuse or on an important topic. This is absolutely not one of those stories. The Hutterites do not need me for anything. If anything, you know, I think in the beginning I thought that they would put up with my intrusion and my curiosity, especially nowadays with social media. The Hutterites are very good at telling their own story and stuff, and they do it beautifully while still holding on to their own privacy and stuff like that. So, I wouldn’t say that my work has changed anything in the community. And I wouldn’t expect it to at all, but I am grateful that a lot of people know about my work and have been very kind about it and enjoy seeing representations of themselves out in the world.

6) Do you believe that journalism still has the power of change?

Sure. Yeah, I absolutely do believe in it. I believe in storytelling. And I think that storytelling is such an important part of human culture, whether it’s through music, art, journalism. I think there are so many ways of storytelling and I think journalism is an important aspect of democracy and being able to tell stories that may not otherwise be told. And I absolutely do believe in the importance of it despite the difficulties that the industry is facing right now. It seems to be harder and harder these days to be a journalist. I would say the diversity of journalists telling stories from around the world is probably better than it’s ever been in history, and I think that’s important.

7) Do you think that because of the social media, and everyone is exposed now, it made it easy for everyone to be a journalist or a storyteller?

I think it’s kind of a double-edged sword because I think it’s great, because now everyone has a way to tell their own story or to tell stories and to put them out there, and I think that’s fantastic, and everyone has a camera in their back pocket now, and I think that’s so cool. I think it makes it more difficult for stories to be recognized because there’s so much out there now. But I do see a lot of beautiful work being recognized, and I think it’s wonderful.

8) Have you faced anything dangerous while documenting these projects?

Yeah, absolutely. Not dangerous. There’s been nothing dangerous about this project that I’ve done. The only thing I can think of that is hard about this project is getting to know people over the long term and becoming, you know, friends and close and then sometimes losing people to tragedy and things like that, which is painful. So, I try to respect what people feel about it. If someone doesn’t want their photo taken, then that’s completely their choice and I must respect it. But I’m lucky that over the years a lot of people have allowed me to take photos of their lives.

9) What differences came to your life before and after COVID?

I think I value the importance of connection more. And the one thing I learned from the pandemic is that it’s OK to slow down and that, you know, your work life isn’t everything. I think the pandemic forced me to slow down my work life and to get back into other aspects of my life that I really enjoy, like skateboarding and visiting with friends and family and things like that, which maybe sometimes I get too busy for work. So, I think it’s important, especially in journalism, because it can be so demanding. I think it’s important to balance that with a normal life and with other hobbies and things like that. It really slowed down my work for two years, but now things are busy, and it seems to be going well. So, I’m lucky that things have kind of rebounded.

10) What other projects have you done?

My other projects are about documenting prairie culture, which is about 15 years old as well. These are my two longest projects by far. But I’ve done a few projects over a few years. I did a project on a mother and son who had cancer at the same time. That project took about a year. I did a project just about a man who lived alone on a farm north of where I live. I photographed him over a few years and then a couple of other projects here and there that I’ve photographed over a few years. But my Hunter-Eye project and my Prairie project are by far the longest projects I’ve worked on.

11) Do you like to get attached to people documenting their stories?

I do, yeah, absolutely. I think it’s important to spend that time getting to know someone well. And I think that really helps my work.

12) Will you tell me more about the man who documented his life and who passed away?

The story started when I was a kid. I recognized this bright red barn that had Bible scripture written on the barn. It had a Bible quote that said, what shall it profit a man to gain the whole world but lose his soul. We would pass this barn every spring when we went up to Clear Lake because my dad always played in a golf tournament every May. So, we would go up there and we would pass this barn.

I remember as a kid just being so interested in the story of this barn. And then in 2007, when I moved to Brandon, I went up to Clear Lake for an assignment, and then I saw that barn for the first time in years, and it reminded me of when I was a kid. So, I, being a curious journalist, I wanted to know the story of the barn. And I heard that there was a man that lived on this property in a house up in the woods away from the road. And one day I went up there, and I walked up the pathway through the forest to his home and I knocked on the door and introduced myself and that’s how I got to know Claire. Claire had lived there long, and he hitchhiked everywhere that he went.

He collected all his food from either donations or from scavenging food in dumpsters outside of grocery stores and things like that. So, he collected all his food for free. He spent most of his day either out talking to people while hitchhiking to town, collecting food, reading the Bible, praying, cutting firewood in his forest, or visiting with his over 30 cats that he had. He was an incredible person. He had an incredible story. It was very complicated. Claire also dealt with mental illness that made it very hard for him to lead a normal life. At one time he had a wife, he had He had kids. I know his kids now as well, and he had a normal life. He was a teacher, he was a farmer, he was a baseball player and a curler, and unfortunately, mental illness kind of took that from him, because he chose not to get help for his mental illness. He lost a lot of things in his life, including his family, and not because it wasn’t sustainable, it wasn’t a normal environment for a family and for raising kids, but he chose his own path.

Despite the pain that I think it caused in his life, he was a beautiful path, and he was a very kind and amazing person.

He died almost five years ago now, some March 2019. He died, and it was a real shock, and I miss him every day. He was a good person.

13) What is his medical diagnosis?

I believe it was undiagnosed schizophrenia. That’s what his family told me.

14) Why did you pick the mother and her son as a project?

That project started out of a newspaper assignment when Cheryl the mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and at that point her son already had leukemia. I went there for the newspaper to take a picture of them for a fundraiser that was being held. I went to take photos for the newspaper of Cheryl and her kid and this was right at the very start of Cheryl’s way of dealing with cancer.

She had just been diagnosed with breast cancer, so I went, and I took some photos, and I was only there for about an hour, but we kind of had a good relationship. They were very easy to get to know, and we were kind of joking while we took pictures and stuff, and I just thought that I thought it would be an important story to tell and that they would be a good family to tell it. I reached out to Cheryl, and I asked if I could kind of spend the year documenting their story while Cheryl and Colin went through treatment.

15) Are they still alive?

Yeah, they’ve been treated. Luckily, that’s a happy story. Cheryl had double mastectomy surgery, and she did chemotherapy and Colin was in chemotherapy for a couple of years, but now they are both healthy and happy and cancer free. They survived, both beat cancer, and they’re both doing very well in the family as well.

16) Are you from the happy journalists or the sad journalists, like the ones with families, friends and living their best lives, or the lonely, sad ones and their job affected their personal lives?

That’s a great question. I think I’m both, but I’m trying to be the happy journalist. I have a family that I love very much, friends and job I learned from it a lot. My son is in his third year of architecture at university and his mom and I are very proud of him. Looking forward to him coming home for Christmas.

17) Between past and upcoming projects, what’s new?!

This year was very busy and full of different projects, and one of my Hutterite project photos from Montana was published in National Geographic Magazine in August. Some of my projects have been connected since the Fall of 2023, when I traveled to Germany, Austria, and Italy for exhibitions.

I’m looking for a book publisher for my Hutterite project and continuing work on it. I did a new small three-month project this summer called Chaff – A Harvest Project. Also, recently, I did some work in northern Manitoba for a really good Narwhal story. My exhibitions were in Italy, Greece, Finland, and Canada. My future exhibitions will be in 2025 UK ( Photo Form Festival), Germany, the USA, Canada, and Romania.

Conclusion:

A Canadian photojournalist who spent years of his life on an important project that documented the lives of isolated groups in small villages in Canada. And did many exhibitions around the world. His use of the camera had changed the new perspectives of new media in considering photography a simple way of capturing memories only. These photos of Tim are living memories of people who passed away and others are still alive. Storytelling of emotional stories and strong bonded communities. That reminds us how socializing, slow living, reconnecting and communication are important and how life was before and after the pandemic of COVID- 19 and how it impacted people’s lives, choices and goals.